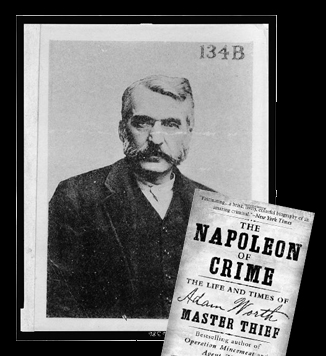

Adam Worth, sometimes given the same epithet as the fictional villian who challenged Sherlock Holmes, “The Napoleon of Crime”, was a German-born criminal mastermind.

Worth was born in Germany in 1844, the first child of a poor Jewish family; his original surname is believed to have been “Werth” or “Wirtz”. When he was five years old, he and his parents moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where his father got a job as a tailor. Worth spent his childhood as a part of the Jewish working class. At the age of 14, he ran away from home and went to Boston. A few years later, in 1860, he moved to New York City. It was there that he had what he later called his “first and only honest job” as a clerk at a department store, which he held for only a month. In 1861, when Worth was 17, the Civil War broke out. Lying about his age, he enlisted in the Union army, partly because he wanted the adventure but also because of the $1000 bounty he was paid. He served in the 34th Light Artillery regiment of Flushing, New York and was promoted to the rank of corporal and then sergeant within months. He was put in charge of a cannon battery and led his troops in several fights against Robert E. Lee’s soldiers. In August of 1862, he was injured by shrapnel during the Second Battle of Bull Run in Virginia and was shipped to Georgetown Hospital near Washington D.C. While recovering, he learned that he had accidentally been listed as killed in action and seized the oppurtunity to leave the Army.

After being declared dead, the criminal comes of age

After being declared dead, Worth became a bounty jumper and started enlisting in various regiments under assumed names, serving in it long enough to receive his bounty. He occasionally took part in full-on combat even though he detested violence, and then deserting with the money. As a result of these activities, he was eventually pursued by the Pinkerton Agency, but slipped away from them on several occasions. Giving up his bounty jumping, Worth went to New York City, which during the post-war years was teeming with illegal prostitution, gambling, and liquor. Though neither a drinker nor a gambler, Worth worked his way up among the gangs of the underworld. He began working for other criminals as a pickpocket before establishing his own gang of pickpockets and becoming a planner and financier of heists. However, he was arrested while taking part in a cash box theft from an Adams Express wagon. He was sentenced to three years of hard labor at Sing Sing, but escaped after only a few weeks. In order to change his appearance, he grew a mustache and a pair of mutton chops.

Worth also stopped operating as a freelancer and started working for Fredericka “Marm” Mandelbaum, one of New York City’s most infamous fences and criminal financiers. During his time working for her, Worth strived to improve the criminal techniques of his time and to make them more effective and safer. During the later half of the 1860s, he masterminded several heists and robberies. In 1869, Worth was hired along with Max “The Baron” Shinburn to spring a robber named Piano Charley Bullard out of jail. They did so by paying off the necessary guards and digging a tunnel under the jailhouse walls. Though the collaboration was a success, Worth and Shinburn became rivals afterwards with Worth always surpassing Shinburn. However, Worth and Bullard became partners for a long time afterwards. Together, they robbed the Boylston National Bank in Boston in November of 1869 by setting up a fake health tonic shop next door and digging through the wall. When the Pinkerton Agency came down hard on the investigation and tracked the shipment of trunks from the storefront to Worth and Bullard, they left town and went to Europe. They spent the following years living under the respective aliases “Henry Judson Raymond”, a financier from the East coast, and “Charles H. Wells”, an oil magnate from Texas.

EuropeEdit

Worth and Bullard went ashore in Liverpool, England, where they met a barmaid named Kitty Flynn, whom they both wooed. Despite being told their true identities, she wound up marrying Bullard, though Worth never resented him for it. They eventually had two daughters together. While they were on their honeymoon, Worth robbed a number of pawn shops, eventually dividing the loot with the couple when they came back. Shortly afterwards, in 1871, all three moved to Paris together. With what was left of the loot from the bank heist, they bought an abandoned three-floor building near the Paris Opera House and turned into the “American Bar”, a bar and restaurant with an illegal gambling den on an upper floor. The gambling tables were constructed so they could be easily concealed and the guests could pretend to be doing something else. The place attracted several guests, honest people and criminals alike. Among the guests were employees of the Boylston National Bank, who had no idea who owned the place they patronized. The bar flourished until 1873, when one of the Pinkertons (some sources say it was the founder, Allan Pinkerton, while others say it was his son, William) came into the bar. As Worth suspected that they were on to him, he and the Bullards decided that they would have to close the bar. They did however put it to use one more time to rob a customer, a jewelry salesman, of a bag of diamonds worth thousands on closing night.

After the assets were liquidated, Worth and the Bullards moved to London, where they bought the Western Lodge, a Georgian mansion house, at Clapham Common and Worth leased an apartment in Mayfair, London’s most fashionable district. While leading a double life in the high society as “Henry J. Raymond”, Worth formed a vast criminal syndicate and ran it through trusted intermediaries. None of the people who actively took part in his operations, which mainly included robberies, armed and otherwise, and burglaries, but also larceny, safe-cracking, and swindling, knew the identity of the man behind it all and were forbidden from using violence.

At one point during this time in Worth’s career, his brother, John, sought him out in England hoping for a job and became involved in an international forgery scheme. Having received an amount of English cash, John was sent to Paris to exchange the pounds for francs. Unfortunately, he accidentally went to one of the banks he had been warned against using. When the bank discovered that the bill of exchange was fake, John was arrested and extradited to England into the custody of John Shore, one of Worth’s most persistent adversaries. However, worth was able to provide his brother with a good legal defense and get him acquitted in court and then sent him back to the States. On another occasion, four of Worth’s most trusted employees were arrested in Turkey after carelessly spending a lot of forged credit notes all over Europe. They were convicted and sentenced to seven years of hard labor in prison, but Worth was able to bribe the right officials and get them released before the Pinkerton Agency could get them extradited to the U.S.

In 1876, Worth organized one of the most notorious heists of his career, one of the few in which he personally took part. That year, a painting of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Cavendish by 18th century artist Thomas Gainsborough reemerged. After being bought at an auction by art dealer Thomas Agnew and sold for 10,000 guineas, it was put in his art gallery. Upon seeing the painting, Worth took a liking to it and hired Jack “Junka” Phillips, his bodyguard, and “Little Joe” Elliott, another of his associates, to join him in breaking into the gallery and stealing the painting. However, though he told the people who worked for him that he would sell it within a few months, he never did so. Eventually, Junka and Little Joe became impatient. So much that Junka tried to trick Worth into talking about the heist in front of an undercover policeman at a bar. Upon realizing what he was doing, Worth knocked the table on top of Phillips. He never associated with him again. Worth then gave Little Joe money he had asked for to return to the States, where he was arrested for robbing the Union Trust Company. When he was put in prison, he told the Pinkerton Agency about Worth’s activities. They notified Scotland Yard, but since Elliot had no idea where the portrait was being kept (he had hidden it in various locations in his mansion and concealed it in a custom-made briefcase when he was travelling) and both agencies were already aware that Worth was a criminal, nothing came of it.

Worth sought to regain some funds that had been lost in the Turkey incident. He and a group of followers went to Cape Town, South Africa to look into the possibility of exploiting the local diamond mining. Eventually, Worth and an accomplice, Charley King, tried to rob a horse-drawn wagon transporting uncut diamonds at gunpoint, but were fought off by the guards. King fled far away, but Worth stayed in the area. He planned another robbery, using a more sophisticated approach. Posing as a feather merchant, he befriended the postmaster of the local post office, where the diamonds were to be stored if they missed the ferry to England. While alone in the postmaster’s office, Worth made a wax impression of his key and had a copy made. When the next diamond transport was due, he beat it to the harbor and cut the express ferry loose. The diamonds were then stored in the post office. Overnight, Worth robbed the post office’s safe and stole the diamonds, valued at $500,000, and returned to London, where he used a new associate, Ned Wynert, to open up a jewelry store and sell the loot from Africa at lower prices than the competition.

Sometime in the early 1880s, Worth got married. The bride, whose name remains unknown, was the daughter of a family whose lodging house Worth had stayed at when he first came to the country. They had two children together, a son named Harry in 1888 and a daughter named Constance in 1891. In September of 1892, Worth went to Liege, Belgium, where he found out that Bullard had passed away. Impulsively, he concocted a haphazard plan to rob a money transport, aided by Johnny Curtin, an American bankrobber, and Alonzo Henne, a Dutch small-time crook. On October 5, they carried out the robbery. However, they were spotted and Worth was apprehended by the gendarmes. He was held in prison for a week, refusing to admit to any crime or even reveal his name. When the Belgian authorities circulated photos of him to European and American investigators, the NYPD and Scotland Yard caught on to him. Most shockingly, his rival and former associate Max Shinburn made contact with the police and gave a testimony of everything he knew about Worth and his crimes. His trial began on March 20, 1893, where he kept flatly denying all the accusations and claiming the botched Liege heist was a desperate act done because he needed the money. Ultimately, he was found guilty of robbery and sentenced to seven years in Leuven prison.

RetirementEdit

The time in prison was awful for Worth, not just because his authority was taken away from him, but also because Shinburn, who was given a reduced sentence of one year in exchange for his testimony, hired people within the prison to abuse Worth whenever he could afford it. Later, Worth received word that his wife had been date-raped by Johnny Curtin, after which she had become insane and committed to an asylum. Their two children were left in the care of Worth’s brother in New York. In 1894, Marm Mandelbaum and Kitty Flynn both died of illness. In the fall of 1897, Worth was released early for good behavior. Determined to have his children grow up to have a different career than him, he robbed a diamond store in London to get enough money to go to America. After bidding his institutionalized wife goodbye, he left and visited his children. Afterwards, he visited the Pinkertons in Chicago.

Worth admitted to possessing the portrait of the Duchess and offered to return it to Thomas Agnew and give the Pinkertons the credit for finding it. If and only if, he got immunity from prosecution and $25,000 from Agnew. All parties involved agreed to the terms since everyone would benefit from it and the painting was returned. Worth spent the rest of his life living in London with his children. He died on January 8, 1902 and was buried under the alias “Henry J. Raymond”. His son, Harry, handled his estate and funeral, paid for his and his sister’s move to the U.S. and got a job at a foundry. However, William Pinkerton, as part of a deal he made with Worth, got him a better job as a career Pinkerton agent. I cannot help but wonder if the younger Worth prospered in the position his father’s criminal skills had purchased for him.

Many believe that Worth was the inspiration for Conan Doyle’s “Professor Moriarty,” the arch villian of the Sherlock Holmes stories. It is an odd kind of immortality to be the inspiration of an arch fiend in one of the world’s most widely read, and now seen, crime story series. “Moriarty” most recently appeared on the television show, Sherlock, though his gender was changed, I suppose to create a more interesting and surprising character for modern viewers. I can’t help but wonder if Worth was really as smart and dangerous as Moriarty or whether Doyle had to work hard to make him enough of a super villian to face the greatest detective of all times. But when I think of how Worth used a known stolen painting to extort money from the Pinkerton Dective Agency (the greatest of the 19th century), I must admit that Woth did have the dash of Moriarty, himself.

For more on Victorian crime, criminals and crime literature:Alan_McKee_Crime

You must be logged in to post a comment.